About the Catchment

Location | Traditional Owners | Climate | Geology | Geomorphology | Hydrology | Soils | Vegetation

Location

Please note: The following information was produced as part of a scoping report about the Emu Swamp Creek Catchment within the Capertee Valley. Some of the information is specific to the Emu Swamp Creek Catchment, but much of it is relevant to the whole Capertee Valley. Please cross-reference with the interactive map, which can be found here.

The Emu Swamp Creek Catchment sits between Capertee and Glen Alice in the Capertee Valley, northwest of Sydney (Figure 1). The headwaters reach an elevation of over 1,000m at Genowlan Mountain in Mugii Murum-ban State Conservation Area. The mouth of Emu Swamp Creek, at an elevation of 300m, is approximately 2km south of Glen Alice. Emu Swamp Creek is a tributary of the Capertee River, which is an important catchment for the Sydney Basin. The Emu Swamp Creek Catchment area is approximately 2700 ha.

Figure 1. Location of Emu Swamp Creek Catchment

Climate

The region has a temperate climate, with cold winters and warm summers. On average, daily maximum temperature reaches 24.3oC in summer and 9.3oC in winter. Over the year, there is a mean of 44 days that reach below 2oc, and 16 days that reach below 0oC.

The region receives an average of 950mm of rainfall each year. The driest year on record was 2019 with 581.4mm, and the wettest year was 2010, with 1535.2mm. Rainfall is summer dominant, and wind tends to be easterly in the warmer months. In winter, wind is predominately Westerly.

Hydrology

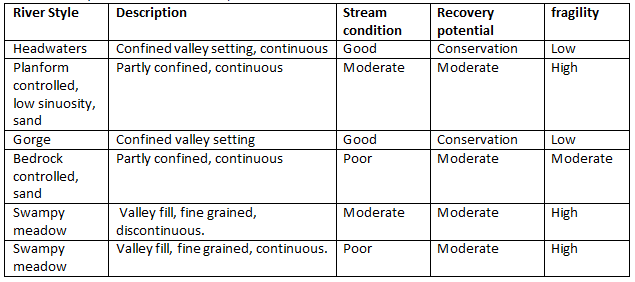

River Styles is a framework used for describing the character, condition and recovery potential of a stream within a given valley setting. A 2001 River Styles assessment undertaken for the Emu Swamp Creek catchment showed five distinct River Styles throughout the length of Emu Swamp Creek (Table 1).

Table 1. River Styles within the Emu Swamp Creek catchment.

Soils

There are nine distinct soil types within the Emu Creek Swamp catchment (Figure 2). Each soil type is a reflection of five key factors;

Parent material (directly beneath if it is an insitu soil, or upslope if it is an alluvial soil)

Climate (rainfall, temperature range, wind)

Slope and aspect

Plant and animal activity both surface and subsurface

Time

Four of the soil types (Hassans Walls, Mt Tomah, Warragamba, and Wallangambie) are directly associated with the Sandstone escarpment country at the top of the catchment. Hassans Walls (Figure 2) is the soil type given to the talus slopes immediately beneath the sandstone cliffs that suround Capertee Valley. While these soils sit over the Permian sediments that contain the coal measures, their parent material is derived from the breaking away and weathering of the sandstone cliffs above them. For this reason, they are known as colluvial soils. They are generally steep, deep and quite extensive within the Capertee Valley.

Figure 2. Soil Landscapes of Emu Swamp Creek Catchment

Vegetation

Vegetation is a critical factor in determining whether any floodplain is building or eroding. Vegetation binds the soil, filters sediments and, as a critical component of the water cycle, dissipates solar and gravitational energy. The vegetation communities of a ‘discontinuous valley floor’ system generally have a mosaic patterning that is determined by hydrology. Western Slopes Grassy Woodlands are scattered across the lower wider area of the catchment, with the Emu Swamp channel often being dominated by Eastern Riverine Forests. The steeper area of the catchment has various types of sclerophyll forest, and heaths where there might be groundwater discharge on Genowlan Mountain. However, over 50% of the catchment is cleared agricultural land.

Geology

The Capertee Valley is a geodiverse region, with rock layers spanning over 420 MY BP (million years before present). Research in the region suggests that the basement of the Capertee Valley is an extension of the Lachlan fold belt, comprising Devonian, Silurian and Ordovician sediments and volcanics (450 -340 MY BP).

Geomorphology

The sandstone aprons that surround the valley and gorges were carved through the power of water and gravity during the Cenozoic Era (66MY BP to the present day) (Rowling 2018). Water erodes the softer Permian shales and coals, causing the sandstone caps to become sheer and eventually dislodge in large blocks. The catchment has a high gradient and variably sized valley floor, making it vulnerable to erosive processes. Headwaters in the Capertee often gain high velocity as they move through the valley. This has created dramatic geomorphic features, from pagoda rock formations to slot canyons (Washington and Wray 2011). These processes have also formed narrow dendritic drainage patterns throughout the Emu Swamp Valley, and across the Capertee Valley more broadly.

Traditional Owners

The Capertee is the custodial land of the Dabee clan of the Wiradjuri nation.

McCarthy (1964) provides important insight into Indigenous history in the Capertee Valley. According to McCarthy, many of the rock shelters near water and gorges in the valley were occupied. This occupation occurred from the slopes to the ridges, which means the population was large enough for groups to spread out from the rugged gorges to the broad valleys (McCarthy 1964).

Dabee peoples in the Capertee Valley had a strong economy due to the abundance food and shelter. Round axes excavated by McCarty were not of local origin, suggesting trade from east or west. Excavated sites show a varied diet, from kangaroo, wallaby, emu, possum, as well as fragments of emu shells and mussels (McCarthy 1964).